Whispers of the Red Dust: Ancient Wisdom and Modern Resolve in the Hunt for Gus Lamont

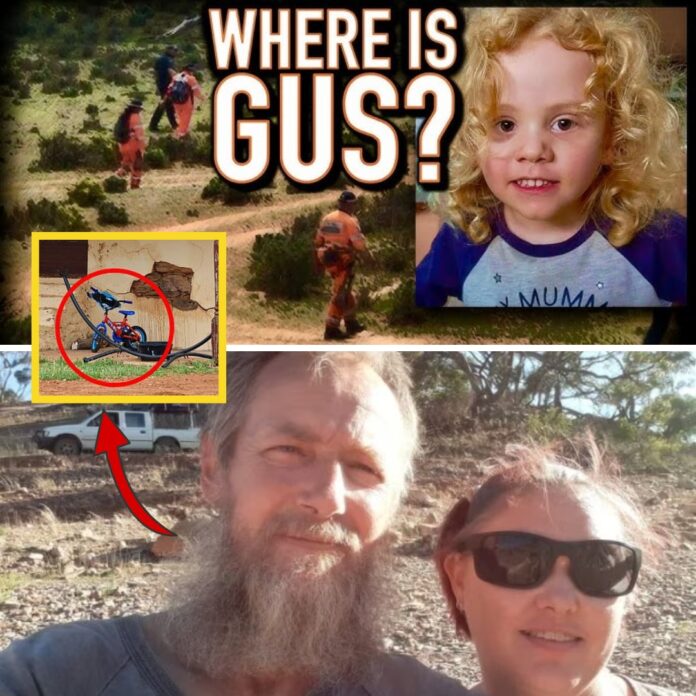

In the vast, unforgiving expanse of Australia’s Outback, where the horizon stretches like an endless red sea and the sun scorches the earth into silence, a four-year-old boy’s disappearance has gripped the nation. Augustus “Gus” Lamont vanished without a trace on September 27, 2025, from the remote Oak Park sheep station near Yunta, South Australia—a sprawling 60,000-hectare property 280 kilometers north of Adelaide. Last seen playing in a mound of dirt outside his grandparents’ modest homestead around 5 p.m., the shy yet adventurous toddler was wearing a blue long-sleeve T-shirt emblazoned with a yellow Minion, light grey pants, boots, and a grey hat. His mother, Jessica Murray, and step-grandparent Josie were tending to the sheep herd 10 kilometers away, leaving Gus in the care of his grandmother, Shannon Murray. What began as a frantic family search in the fading twilight has evolved into a desperate, multi-phase operation blending cutting-edge technology with the timeless lore of Indigenous trackers. As hope flickers amid the red desert’s secrets, the story of Gus Lamont underscores the Outback’s dual nature: a cradle of life for those who know its rhythms, and a merciless devourer of the unwary.

The initial hours of Gus’s disappearance were a blur of parental panic and rural self-reliance. Shannon Murray stepped outside at 5:30 p.m. to call her grandson in for dinner, only to find the yard eerily empty. The family combed the property for three hours—two of them in encroaching darkness after sunset at 6:15 p.m.—before dialing South Australia Police (SAPOL) around 8:30 p.m. “We always believe Gus is a tough little country lad,” a family spokesperson later told reporters, clinging to the image of a boy raised amid the hardy rhythms of station life. But as night deepened, the calls of “Gus! Gus!” echoed unanswered across the spinifex and saltbush, swallowed by the wind.

By dawn on September 28, SAPOL had mobilized a formidable response. The first search phase drew over 100 personnel, including State Emergency Service (SES) volunteers, trail bike and all-terrain vehicle (ATV) teams, and infrared-equipped drones scanning the thermal signatures of the arid terrain. Helicopters from PolAir thumped overhead, their spotlights carving through the pre-dawn gloom, while sniffer dogs strained at leashes, noses to the dust. A single, tantalizing footprint—small enough to spark fleeting optimism—was discovered near a dam 5.5 kilometers west of the homestead, prompting a secondary sweep on October 6. Yet forensic analysis dashed hopes: it wasn’t Gus’s.

As the days stretched into a week, the operation escalated. On October 2, 48 members of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) deployed from nearby bases, fanning out in grid patterns across 95 square kilometers of parched earth. Police cadets from Adelaide bolstered the ranks, their boots kicking up red ochre clouds. Community members from Yunta—a speck of a town with just 100 souls—joined the fray, their 4WDs rumbling over gibber plains. Drones buzzed like mechanical cicadas, mapping crevices where a child might hide, while experts from the Australian Missing Persons Register weighed in on behavioral patterns: “Not everybody who goes missing is the victim of foul play,” noted director Nicole Morris. “Sometimes children just wander off, especially on such a large property.”

Yet for all its high-tech arsenal, the modern machinery faltered against the Outback’s ancient cunning. The landscape here is a labyrinth of deceptive simplicity: flat mallee scrub dotted with wombat burrows, ephemeral creek beds that vanish after rain, and salt pans that mirage like water under the relentless sun. Temperatures that day hovered at 28°C (82°F), dropping to 12°C (54°F) at night—survivable for an adult, but a gauntlet for a four-year-old clad in layers against the chill. Human physiology expert Nina Siversten later theorized Gus might have ventured 3 to 8 kilometers beyond initial grids in his first three days, sustained by dew on leaves or instinctual foraging, before dehydration or exposure claimed him. “Fear would impact movement, but also drive him toward shelter,” she said, evoking the primal terror of a child adrift in a world of giants.

It was here, amid the limitations of gadgets and grids, that ancient knowledge entered the fray—a poignant fusion of eras. On October 2, following the discovery of that elusive print, SAPOL enlisted Ronald Boland, a 58-year-old Aboriginal tracker from Port Augusta with deep roots in Nukunu, Narungga, and Kokatha heritage. Boland, a trapper by trade, arrived not with maps or monitors, but with eyes honed by generations: “All my teaching comes from Aboriginal people in the north of South Australia,” he told the Daily Mail on the one-month anniversary. “I was taught the ways by those old traditional Aboriginal stockmen.”

Aboriginal tracking, an art form etched into Australia’s colonial and pre-colonial history, traces its lineage to the continent’s first peoples, who navigated by star maps, animal trails, and the subtlest disturbances in the soil. European settlers quickly recognized its value; from the 1830s, trackers like Mogo and Mollydobbin in Western Australia located lost children after hours in the bush, while in 1864, Dick-a-Dick found the Duff siblings after nine days in Victoria’s Wimmera. South Australia Police once employed 65 such specialists, none more legendary than Jimmy James, who in 1966 rescued seven-year-old Wendy Pfeiffer after 150 others failed. Today, though no longer formally on payrolls, trackers like Boland bridge worlds, their skills preserved against cultural erosion.

Boland’s methods are a masterclass in subtlety. He moves low and slow, scanning not just footprints but the “tell” of bent grasses, displaced pebbles, or the faint oil sheen of a child’s skin on bark. “We read the country like a book,” he explains, invoking techniques passed down through hide-and-seek games near Coober Pedy, where opal miners’ children vanished into dunes. In Gus’s case, Boland scoured the dam’s edges and wadi-like gullies, discerning kangaroo pads from human treads by pressure patterns and toe splay. One cryptic remark lingers: “That little boy deserves respect to go about it on all the right roads. Police will find him, they will. They do what I do best, I do what I do best.” His quiet confidence—that the land “reveals what it swallows” in time—has buoyed searchers, even as it hints at unspoken insights.

The intersection of Boland’s lore with modern teams has been electric, if uneven. ADF soldiers, trained in urban warfare, deferred to his reads on wind-eroded tracks; drone pilots adjusted flights based on his flagged “hot zones.” Yet tensions simmered. SES veteran Jason O’Connell, who logged 90 hours and 1,200 kilometers on his bike, voiced a haunting doubt: “I don’t believe he’s even there anymore.” The family, too, bristled under scrutiny. On October 31, as a third search phase kicked off—complete with draining the suspect dam—grandmother Shannon Murray brandished a shotgun at a trespassing reporter, her voice cracking: “Get off our land!” Father Joshua Lamont, estranged and living two hours away in Belalie North, clashed with Josie over the boys’ remote upbringing, learning of Gus’s vanishing not from kin, but police. Online whispers—fueled by X (formerly Twitter) threads speculating on family dynamics—have veered into the cruel, with some eyeing Josie’s cross-dressing as a red herring of suspicion. SAPOL, under Task Force Horizon, insists: no foul play suspected, just a boy who wandered.

By mid-October, the search pivoted from rescue to recovery. Medical experts pegged survival at three days without water in that heat, prompting scale-back on October 7. The dam draining on October 31—its waters previously dived but not fully plumbed—yielded mud and murmurs, but no Gus. Police Commissioner Grant Stevens captured the family’s torment: “This would be traumatic for any family.” Friends like Fleur Tiver decry the speculation: “There is no way they’ve harmed this child.”

As November dawns, the Outback holds its breath. Boland, now mentoring youth to safeguard his craft, embodies a resilient hope: “One day I will tell the story.” In this red desert crucible, where drones hum hymns to progress and trackers whisper to the wind, Gus Lamont’s fate remains a riddle. The land that birthed Australia’s stories may yet yield its latest chapter—one of loss, legacy, and the unyielding human spirit.