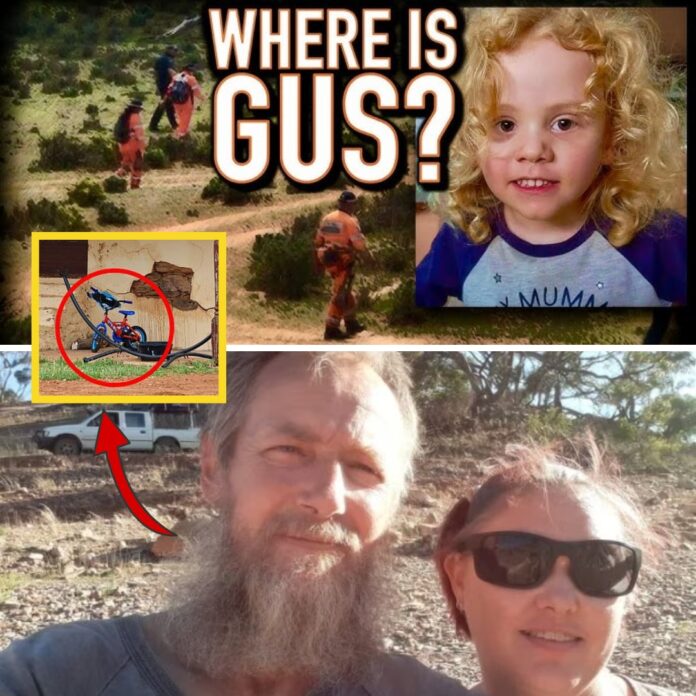

“If His Little Feet Touched This Land, We Will Know.”

Dawn breaks as trackers trace faint marks along a dry creek bed. With the blessing of local elders, the search for 4-year-old Gus enters a spiritual phase—where instinct and earth speak louder than maps…

The first light of November 2, 2025, spills like molten copper across the gibber plains south of Yunta, South Australia. At 5:47 a.m., when the temperature still clings to a merciful 14 °C, a small convoy of 4WD utes noses through a gate on Oak Park station and stops beside a bone-dry creek bed the locals call Wandalla Gully. The gully is a scar of red sand and cracked clay, 2.3 metres wide at its broadest, snaking west-north-west for seven kilometres before it vanishes into a salt pan. Thirty-five days have passed since four-year-old Augustus “Gus” Lamont vanished from the homestead yard. Every grid square within a 12-kilometre radius has been walked, flown, sniffed, scanned, and drained. Yet here, in the hush before the heat, something new is stirring.

Ronald Boland, the Kokatha tracker who first joined the search on October 2, kneels at the creek’s lip. His calloused fingers hover an inch above the surface, not touching, simply feeling the air’s memory. Behind him stand three Adnyamathanha elders—Aunty Evelyn Karpany, Uncle Reggie Wilton, and 29-year-old cultural ranger Tjarutja Dodd—plus two SAPOL detectives in plain clothes and a silent drone pilot. No media. No ADF column. Just the land and those who still know how to ask it questions.

“If his little feet touched this land,” Aunty Ev says, voice low as river stones, “we will know.”

The Night Before: A Blessing in Smoke

The decision to return to Wandalla Gully came not from satellite imagery but from ceremony. At sunset on November 1, after the third-phase dam-drain yielded only rusted fencing wire and the skeleton of a long-dead roo, the elders requested a private inma—a short song cycle—on the homestead veranda. Jessica Murray, Gus’s mother, sat wrapped in a blanket, clutching the Minions T-shirt her son wore the day he disappeared. Shannon Murray, the grandmother who last saw him alive, stood apart, shotgun now surrendered to police, eyes fixed on the darkening scrub.

Uncle Reggie lit a bundle of wilga leaves and river mint. Smoke curled thick and fragrant, carrying the family’s grief upward. Tjarutja sang in Adnyamathanha, a melody older than the fence lines, invoking Viralpinku—the spirit who walks the dry watercourses and guards children who stray. When the final note dissolved, Aunty Ev pressed a coolamon of red ochre into Jessica’s trembling hands.

“Paint the path you want him to follow home,” she instructed. Jessica daubed a single handprint on the veranda post—five small fingers, Gus-sized. The elders nodded. The gully, they said, had called during the song. Something shifted in the wind.

Dawn Tracking: Reading the Country’s Diary

Now, in the half-light, Boland moves first. He is barefoot, soles blackened from decades of reading spinifex. The others follow at a distance, careful not to scuff the canvas he studies.

He stops at a patch of silty sand no larger than a dinner plate. To the untrained eye it is blank. To Boland it is a paragraph:

- A faint crescent heel-drag, 19 cm long—too small for an adult, too deliberate for a roo.

- Three toe impressions, splayed as if the child was running downhill.

- A single spinifex needle bent inward toward the print, not crushed outward by wind.

- Micro-debris: a fleck of blue cotton thread caught on a burr, matching the Minions shirt.

“Boy,” Boland murmurs. “Light. Maybe eight kilo. Moving fast, but not scared yet.”

Uncle Reggie crouches beside him. He licks a finger, holds it aloft. “South-easterly overnight. That thread would’ve blown away if it fell after 10 p.m. Means he was here before dark—maybe 5:30, 5:45.”

Tjarutja marks the spot with a twig topped by a scrap of yellow survey tape—no heavier disturbance than that. The drone lifts silently, programmed to orbit at 40 metres, recording only thermal and visual; its data will be cross-checked later against the elders’ readings.

The Spiritual Phase: When Maps Lie

SAPOL’s original search grids treated the land like a chessboard. Wandalla Gully was walked twice—once on September 29, again October 11—because it lay outside the statistically probable 3 km “wander radius” for a four-year-old. But Adnyamathanha lore does not calculate probability; it listens. Children, they say, follow ngutu—spirit lines that pulse beneath the ground like arteries. Water, even when invisible, is a ngutu. So are songlines. So, sometimes, is fear.

Aunty Ev walks the creek’s thalweg, eyes half-closed, palms open. At a bend where the gully braids into three channels, she stops.

“Here,” she says. “The country breathes different.”

She is right. The sand here is cooler, compacted by underground moisture—a soak, masked by a crust of salt. Boland scrapes with a stick; water seeps, dark and precious. A child dying of thirst would smell it, crawl to it, drink.

Tjarutja kneels, presses his ear to the ground. “No heartbeat,” he reports, meaning no recent animal disturbance. “But the soak remembers a small weight. Maybe two nights ago? No—longer. The crust is knitting back.”

Instinct Over Algorithm

By 7:15 a.m. the sun is a hammer. The team has traced the faint prints 420 metres downstream. They vanish where the gully spills onto a gibber apron—stones the size of fists, polished by millennia of flood. Modern trackers would call it a dead end. Boland calls it a pause.

He stands, shades his eyes, and looks the way elders do—not at the ground but at the shape of the country. To the west, a low ridge of quartzite catches the light like a blade. Between here and there: 1.8 km of open saltbush, dotted with wombat burrows and the occasional coolibah.

“Kid sees shade,” Boland says. “Sees height. He’ll make for that ridge. Not straight—zigzag, following roo pads. Look for broken sticks, not prints.”

Uncle Reggie nods. “And listen for the birds. Willy-wagtails scold what’s out of place.”

They split into pairs: Boland and Tjarutja sweeping left, Aunty Ev and Uncle Reggie right. The detectives trail with GPS, but the devices stay in pockets. This is not their language.

The Ridge: A Child’s Logic

At 9:03 a.m., Tjarutja’s shout cracks the stillness. He is 1.2 km from the gully, crouched beneath a coolibah whose roots clutch the ridge like fingers. In the soft dust between them:

- A perfect right-hand print, palm and five fingers, pressed deep as if the child sat to rest.

- Beside it, a scatter of eucalyptus leaves arranged in a tiny arc—play, not wind.

- A single boot tread, 16 cm, heel worn on the outer edge—matching the boots Gus wore.

Boland arrives, breathing hard. He does not smile; the find is too fragile. Instead he lays a leaf over the handprint to shield it from the sun, then photographs it with his phone—no flash, no shadow.

Aunty Ev arrives last. She places her own hand over the print. Hers dwarfs it. Tears cut channels through the dust on her cheeks.

“His little feet touched this land,” she whispers. “And the land kept the story.”

What Happens Next

By noon, SAPOL declares a priority micro-grid: 500 m × 500 m centred on the ridge. Drones return with LiDAR. Cadaver dogs are flown in from Adelaide. But the elders insist on one condition: no heavy machinery until a second inma confirms the path. The land, they say, must agree to give up its secret.

Jessica Murray is driven to the site in a police ute. She steps out, barefoot like the trackers, and places her hand in her son’s print. For the first time in 35 days, she speaks without trembling: “Keep going. He’s still walking with us.”

As the sun climbs, the search for Gus Lamont sheds its skin. Maps are folded. Algorithms pause. Instinct and earth—older than satellites, wiser than statistics—take the lead. Somewhere in the red dust, a four-year-old’s giggle still echoes, carried on a wind that only the country, and those who listen, can hear.